Shouhua Wang, Nevada Department of Agriculture

As plant diagnosticians, we all deal with unknowns. This is often the most interesting part of our job, as it gives us a surprise and makes the day memorable when we solve the mystery.

A client submitted dozens of alfalfa seeds for us to identify what type of weed seeds contaminated his alfalfa seeds. Sounds like a very simple case, right? But not necessarily. Only a few of those seeds could be considered non-alfalfa seeds since they were black in color instead of the normal yellow. These unknown seeds (or hereafter “black seeds”) were cylindrical, about the same size, and visually resembled uncooked black rice.

Figure 1. Alfalfa seed sample with the unknown.

By checking our reference seed library, none were even close to this unknown. Then, we began to take the hard-core approach.

First, we placed one black seed under the dissection microscope to view the surface and internal structure. Nothing was particularly unusual, except a thin black layer covering a white core, as if the seed was charcoal coated. This led to our initial thought: These black seeds could be coated seeds, but this was quickly ruled out after a consultation with the client.

Then, we put several black seeds in a petri dish and added water to see if they would become soft or even dissolve. However, the black seeds remained completely solid. Although this did not provide any new information, it reinforced our hypothesis that the black seed was a biological material, instead of a non-biological substance. With this in mind, we promptly began DNA barcoding, using a few black seeds and a few alfalfa seeds (as control). The entire process, from DNA extraction, PCR, preparation for DNA sequencing and analysis of sequence data, went smoothly. At last, we got the result: The normal alfalfa seeds came with a Medicago sativa BLAST search result (no surprise), but the black seeds came with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum.

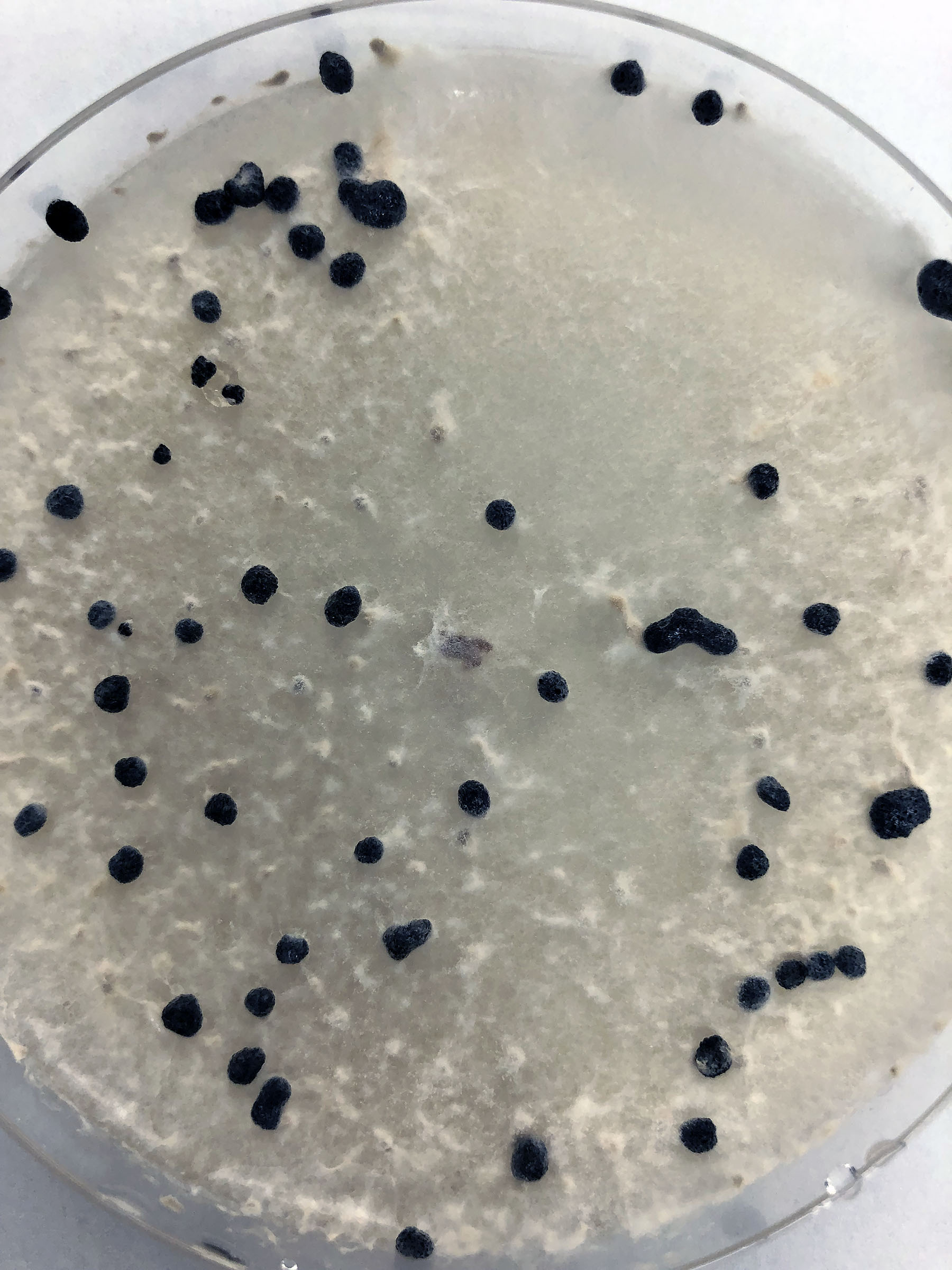

My initial reaction to the result was a little surprise but also disappointment. In our experience of using DNA barcoding to identify unknown plant species and seeds, we find DNA sequences from the plant, plant-associated fungi, or both, because the primers used can amplify both plant and fungal/oomycete DNA. It was possible that the amplification of S. sclerotiorum DNA was due to the fungus contaminating the unknown seeds. So, we went back to the original seed sample, but all black seeds had been used. Fortunately, we had kept the petri dish with the black seeds in water; unexpectedly, grey mycelia were growing out from these black seeds. We transferred each of them to a PDA plate. After 10 days, mycelia covered the entire dish with scattered “black seeds”, but this time, the “seeds” were soft, irregular, and different sized.

Figure 2. Sclerotia produced on a PDA plate.

We realized that the mysterious “black seeds” were the sclerotia of S. sclerotiorum. As such, this mystery of the unknown “seed” species was solved.

Search form

A Diagnostic Surprise on an Unknown Seed

Copyright © 2026. All rights reserved.